Signed and dated 1902

Inscribed on artist’s label on reverse: ‘Bring an offering and come into His Courts’

London, New Gallery, 1903.

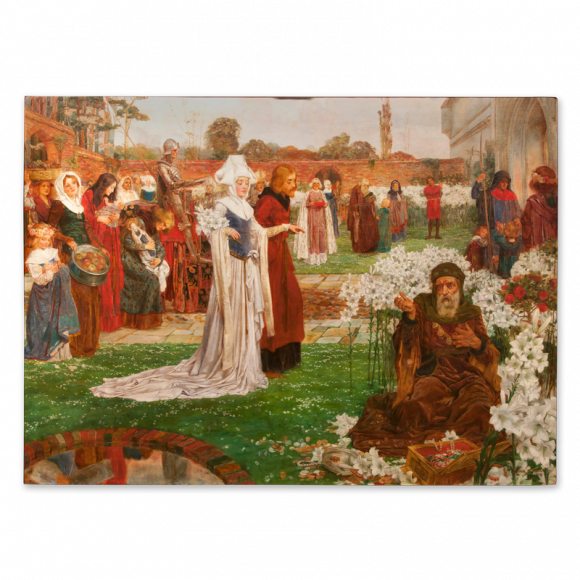

This richly splendid work by Arthur A. Dixon interprets the incantatory ambit of Psalm 96, and specifically line 8: ‘Give unto the LORD the glory due unto his name: bring an offering, and come into his courts’.

Dixon was a painter and illustrator based in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, who specialised in figurative subjects. He exhibited at major London institutions, The Royal Academy and Royal Society of British Artists, as well as the progressive New Gallery. He also illustrated numerous volumes during the golden age of commercial book illustration: 1890-1930. The Dictionary of British Book Illustrators: The Twentieth Century lists over thirty-five editions to which Dixon contributed either all or some of the colour plates, including Blackie’s lavishly produced Bible Stories, as retold by Theodora Wilson Wilson - popular enough to justify several reconstituted versions.* Dixon also illustrated early 20th Century editions of 19th Century novelists such as Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell, and poets, such as John Keats and (the Complete Works of) Alfred, Lord Tennyson. He was commissioned for the re-issues of children’s classics such as Andrew Lang’s Fairy Tales and Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies: a testament to his calibre, as publishers relied upon the visual reinterpretation of well-known tales to lure new buyers. Contemporary press advertisements often printed the illustrator’s name in bolder type than the original author’s.

Dixon is also a standard bearer for a particular form of late 19th/early 20th Century romanticism. This style, which is sometimes termed neo-Pre-Raphaelite, was popularised by a number of artists whose oeuvre encompassed both painting and graphics: Frank Cadogan Cowper, John Byam Shaw, and Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale. More flamboyant than their nominal forbears, they employed bright colour schemes and created populous compositions that put emphasis upon gesture and the grace of the human form. An Offering is representative of the best of this style, being both indebted to Pre-Raphaelitism and subtly modern. Its symbolic complexity shows Dixon’s eruditeness, whilst the lush appeal of the picture as pure artefact proves his worth as a commercially aware painter. Furthermore his figures’ elegant slightness and the dreamy strangeness of the arrangement give a nod towards fin-de-siècle decadence.

Psalm 96 is a celebratory summons to worship as a collective. Lines 7 & 8 of the King James’s Version of the Bible read: ‘Give unto the LORD, O ye kindreds of the people, give unto the LORD glory and strength/ Give unto the LORD the glory due unto his name: bring an offering, and come into his courts’.

Dixon has interpreted this through the figure of a royal court, with the King and Queen leading the procession in worship of the deity. The King, attired in red and black, bows his bare head slightly in deference to the greater God. His Queen, in a pale gown and wimple, carries a bouquet of lilies, which both echo those in the picture’s foreground and the ‘lilies of the field’ from Matthew, verse 28: ‘Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin’. Lilies signified purity and femininity within the secular language of flowers, and had garnered added symbolic potency as a motif of 1860s Aestheticism. In fact, we can see Dixon’s image as paying tribute to Aestheticism, the forbear of Decadence, in more ways than one: the Italianate setting, and the decorative intricacy effected by shifts of texture between brick and petal, flagstone and grass. There are narrative components which comprise mysteries too: the bearded figure in the foreground for example, may be representative of the Psalm singer, as he engages most directly with the viewer and heightens the contrast between the beauties of nature (lilies) with a more material or terrestrial form of wealth (gold coins and jewellery). Dixon may even be casting him in the role of miser, agonizing over the potential giving away of his treasures. The cast gathered behind the royal pair comprise knights and priests, as well as commoners who are shown happily bearing their gifts of carved relics or harvest offerings.

The picture was exhibited at the New Gallery in 1903. Successor to the Grosvenor Gallery, which had opened in 1877 to provide a showcase for the artistic avant-garde, the New retained its predecessor’s values and would have provided a fitting forum for Dixon’s imaginative vision. The painting seems to have numbered one of a pair, or series, since another is on record, probably titled The King’s Garden, featuring a near identical cast of characters. Here the Queen is in the foreground with her arms around a child, and the King is shown watering his plants behind, with courtiers in attendance. The arrangement is less satisfying than Offerings, however, which must number one of the most compelling neo-Pre-Raphaelite works, and arguably Dixon’s masterpiece in oil.

* See Brigid Peppin and Lucy Micklethwait, The Dictionary of British Book Illustrators: the Twentieth Century (London: Murray, 1983), pp. 85-6; Theodora Wilson Wilson, Stories from the Bible Illustrated by Arthur Dixon (London: Blackie & Son, 1914) and Scripture Stories For Children Illustrated by Arthur Dixon (London: Blackie & Son, 1915).